Gary Hardy: The Man Who Saved Sun Records

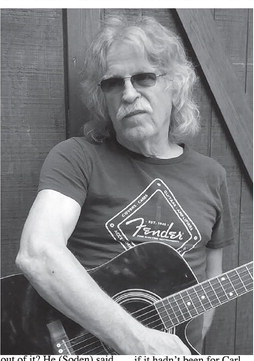

Gary Hardy: The Man Who Saved Sun Records

A fascinating look at the roots of rock and roll and the effort to save music history By Mark Randall

ne ws @ theeveningtimes .com Gary Hardy grew up listening to what he calls his “sister’s music.”

As the youngest child, he got dragged to see Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash shows when they were getting their start on Sun Records in the late 1950s.

In fact, he even got to meet the King of Rock n’ Roll himself – at Graceland.

Little did he know that his sister’s music would eventually become his music, and lead him all the way to Sun Records.

Hardy re-opened Sun Records in the late 1980s when it was all but forgotten, and today is the keeper of the flame, so to speak, of that music.

As the front man of Gary Hardy and the Memphis Two, Hardy keeps the music of Elvis, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis alive every weekend to new audiences at Alfred’s on Beale.

“My sister’s music became my music,” Hardy said. “But it was already our music. If you’re a Beatles fan, this was already your music. It’s really America’s music.

And people come from all over the world right here to Memphis to hear it.”

Hardy grew up in Memphis and aside from living two years in Miami, has been playing music in Memphis since the British Invasion back in the late 1960s.

His sister, who was 12 at the time when Elvis made his first record at Sun, was a big fan of the music being recorded by Sam Philips at 706 Union Avenue.

On Sept. 9, 1954, his grandmother took his sister and a friend to see Elvis perform at the grand opening of Katz Drug Store in the parking lot at the Lamar-Airways Shopping Center. The show drew a large crowd of screaming teenagers.

Being the youngest in the family meant that he had to tag along too.

“I was at Elvis’s first performance,” Hardy said.

“He was on a flat bed trailer and played his two songs over and over. But what I remember, was at the bottom of the Katz Drug store there was an escalator and a candy counter that I couldn’t wait to go to.”

Hardy was at another historic show at Overton Park on August 5, 1955 that featured not only Elvis, but the up and coining Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins.

But again, the historical significance of what he was witnessing did not register on him at the time.

“I was six years old and Overton Park shell is next to the zoo,” Hardy said.

“All I can remember is, why are all these girls screaming? And why can’t I go to the zoo? But those are two very historic events.”

As a teenager, Hardy was more impressed with the Beatles.

His life changed forever when he heard “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” for the very first time.

“My music happened for me when I was 13 years old and heard that song by the Beatles,” Hardy said.

Hardy learned to play the guitar and at age 16 was singing with two legendary Memphis bands “The Guilloteens” and “The Group” out at the Cock and Bull club, which, ironically, was the former Eagle’s Nest where Elvis used to play.

“We were playing strictly songs from the British Invasion and whatever American music was popular at the time in ’68, ’69, and ’70,” Hardy said. “That and Soul music.”

When he came back to Memphis in 1970 from Miami, a bandmate told him that he wanted to show him some place and took him to a boarded up building on Union Avenue.

The building was the former home of Sun Records.

Sam Phillips had moved his studio in 1960 and the place was empty and falling in to disrepair.

“We went around the back and pried open a board and went in,” Hardy said. “I said, ‘where are we?’ He said, ‘You’re where Sun Records used to be.’ The control room had been tom out and in the middle of the studio there was a 1957 Mercedes 190 on blocks. I went, ‘geez, what’s the big deal?’ He kinda agreed. He just wanted me to see it.

It didn’t matter that Elvis played there.

“That tells you how Memphis treated that whole Sun Records era. It was empty and forgotten. There was none of that sense of nostalgia at that time.”

Hardy had no way of knowing it, but he and 706 Union would cross paths again.

But in the 1960s and 70s when he was playing in bands, Elvis was no longer relevant to his generation.

In the summer of 1969, Hardy was hired by his next door neighbor to help shoe horses. One of his clients was none other than Elvis Presley.

“He said, ‘Come on. We’re going to Graceland,”’ Hardy said.

“So I went. He said, ‘Do you want to meet Elvis?’ So as I was cleaning hooves he said ‘Elvis, this is my neighbor, Gary. He’s in town for the summer helping me out.’ I went, ‘Hey, man.’ Not, hello Mr.

Presley. In the late 1960s and early 70s Elvis was not held with great respect in the world of music – especially with the British Invasion. He wasn’t cool at my age.”

Hardy regrets not being more in awe of Elvis and appreciating what a once in a lifetime chance that was.

“I was a cowboy that day,” Hardy said. “That’s the cowboy way. But I regret not taking meeting the King of rock ‘n’ Roll more seriously.

“But you have to understand. Graceland was maybe a half a mile from my grandmother and grandfather’s house. When I was a little boy, there was 100 acres and cattle there.

So meeting Elvis was no big deal at the time.”

Hardy continued to play in bands throughout the late 60s and 70s, but got an idea for an amp stand that he designed which he was able to sell commercially.

At a trade show in Los Angeles, he spotted a girl singing on an early karaoke machine. The unit had a record player on top, a variable speed cassette player on the front, and an eight track player.

He quickly realized that the machine would be perfect for musicians to use to record songs on. He bought every single one they had all 48 – for $94 apiece.

“I thought what a great tool for a singer,” Hardy said. “I’d spent $600 for my first recording session.

With this machine, you could sit at home and sing with this, record tracks.

and get really good.”

Hardy didn’t think karaoke would catch on with Americans. But in 1984 he convinced Elvis Presley Enterprises to let him open an amateur recording studio in their complex across the street from Graceland.

“I researched the technology and made a deal with Panasonic,” Hardy said.

“They had a nice double cassette unit. So I had recording booths and a sound board with 100 tracks on it. You could come in and make a cassette recording at Graceland for $10 in the heart of the complex across from Graceand.”

The venture proved a success. Over the next eight years Hardy made over 10,000 recordings at that studio. Celebrities like Sam Kinnison to Ric Ocasek of The Cars all recorded at his studio.

Then in 1986, Elvis Presley Enterprises CEO Jack Soden called him and asked him if he would be interested in re-opening Sun Records.

Graceland didn’t want it. The City of Memphis didn’t want it. Sam Phillips didn’t want it. Nobody wanted it.

“I said, ‘are you going to be my partner?’” Hardy said. “They said, ‘no, we can’t do that.’ Well, are you going to give me money to finance it? ‘No, we can’t do that.’ Well, what do I get out of it? He (Soden) said, ‘we will talk good about you if you make it work.’” Hardy asked his friends in the recording industry what they thought of the idea and everybody thought it was a bad idea.

He spent whatever money he had and decided to do it anyway. Hardy figured if he could come up with some kind of a tour, that he could make money during the day when the recording studio wasn’t being used.

“I wasn’t trying to save the building because this is where all this great music was made,” Hardy said. “I was trying to make records at night. That was my motive.”

Hardy found some photographs of Elvis and some of the big names who had recorded at Sun, blew them up, and hung them inside where they are still there today.

He only had a few items for the tour – a microphone which was used by WHBQ DJ Dewey Phillips, who was the first to play Elvis’s record ‘That’s All Right,’ an old guitar amp, piano, and a set of Ludwig drums.

Then he waited.

And waited.

No one came by.

“It was hard,” Hardy said.

“People had forgotten what was in the building and didn’t care.”

Graceland was no help.

The City of Memphis was no help. They didn’t even include Sun Studio in their tourism brochure the year it opened. Hardy had to make his own flyers and put them out at all of the hotels to try and drum up tourists.

And still, nobody came that first month.

Hardy was broke by then and was ready to let the bulldozers have the building.

Then one night he got a phone call from a friend that turned things around.

“He said, ‘Gary, 1 hear you have that building where Sun Records used to be.’ I said, ‘yeah, I’m sitting here right now.’ He said ‘I’ve got somebody now who wants to come by.’ I said, ‘You’re a little bit late. I’m about to let them have it. Nobody wants it. Nobody has helped me. All I'm doing is hurting my family.’ He said, ‘No, you’ve got to let me come down.’ I said, ‘well, who is it?’ He said, ‘Ringo Starr.’ I said, ‘Bring him on down.”’ Starr recorded four songs at Sun that night. During a break in the session, Starr told Hardy how much he loved the music that came from Sun Records and that if it hadn’t been for Carl Perkins, there would be no Beatles.

The Beatles recorded a number of Perkins songs including “Honey Don’t” and “Matchbox.”

“I had a man come in here who changed my life when I was 13,” Hardy said. “I had a Beatle come in. It was at that moment that I knew that what happened here in this studio made music history because it made the Beatles.”

Hardy had another music legend drop by as well who was influenced by Sun.

Bob Dylan.

I had another phone call and I wasn’t really ready for anybody else to come by and see the place,” Hardy said. “I said, ‘who is it?’ He said, ‘Bob Dylan.’ I said, ‘bring him down.’” Dylan didn’t record anything at Sun, but Hardy said Dylan brought along a camera.

“He came down and spent about an hour with me and asked a couple of questions,” Hardy said. “But he had a Polaroid with him.

I had six big photographs on the wall from Sun.

One of them is of Elvis at Ellis Auditorium. He said, would you take my picture?’ “I said, ‘why sure.’ He kneeled in front of the picture of Elvis. Kneeled. I was surprised. When he got up he could tell that I was surprised. He looked at me and said, ‘Everybody needs a hero.’” Slowly, the tours started to pick up. And there were other famous artists who dropped by to record. There was a single with Def Leppard. An album with Johnny Rivers.

Bonnie Raitt. Fleetwood Mac. The Eurythmics. Bob

M E M P H I S , T N

blessed that Carl Perkins and I became friends. I produced his last record and he played on dozens for me.

“I would sit in the control room and these guys would come in the back door and come in and sit down and start talking. They heard I was there and that I had it open. They wanted to come back.”

By 1990, Hardy came to realize that Sun Records was a special place.

But just when it seemed that business was picking up and that the tours were a success, high rent and a series of bad business deals forced him to sell Sun Records.

“I trusted the wrong people and lost the studio in a corporate raid in 1995,” Hardy said. “I was basically still an artist who just happened to figure out how to make money. But then I didn’t know what to do when things got bigger.”

Today, Sun Records is one of the top tourist attractions in Memphis. Hardy looks back with pride that he is the one who saved it from the wrecking ball back when no one else cared.

“My view is, I’m not bitter,” Hardy said. “I did that. And it will be there forever. When I got it, it was going to be torn down.

When I left it, it was on the National Historic Registry.”

Hardy went back to making music in 1992 and was one of the first artists to play regularly in the rejuvenated Beale Street clubs.

His Johnny Cash Sun Records tribute show at Alfred’s draws people from all 50 states and around the world.

And who better than to keep the music that made Memphis than the man who re-opened Sun Records.

His sister’s music, is now very much his music.

But it’s really America’s music.

“I love what I do,” Hardy said. “I try and impart the essence of this great music that came from this city as it related to Sun and its artists, and the artists that it influenced, which is just about everybody.”

JANUARY 5-8, 2019

Share